Maximising diagnostic potential: a guide to urinalysis and urine cytology in companion animals

Urinalysis is a vital diagnostic tool for evaluating canine and feline patients. It remains one of the most cost-effective yet valuable diagnostic tests, offering insight into not just urinary and renal conditions but systemic health too.

Indications for urinalysis

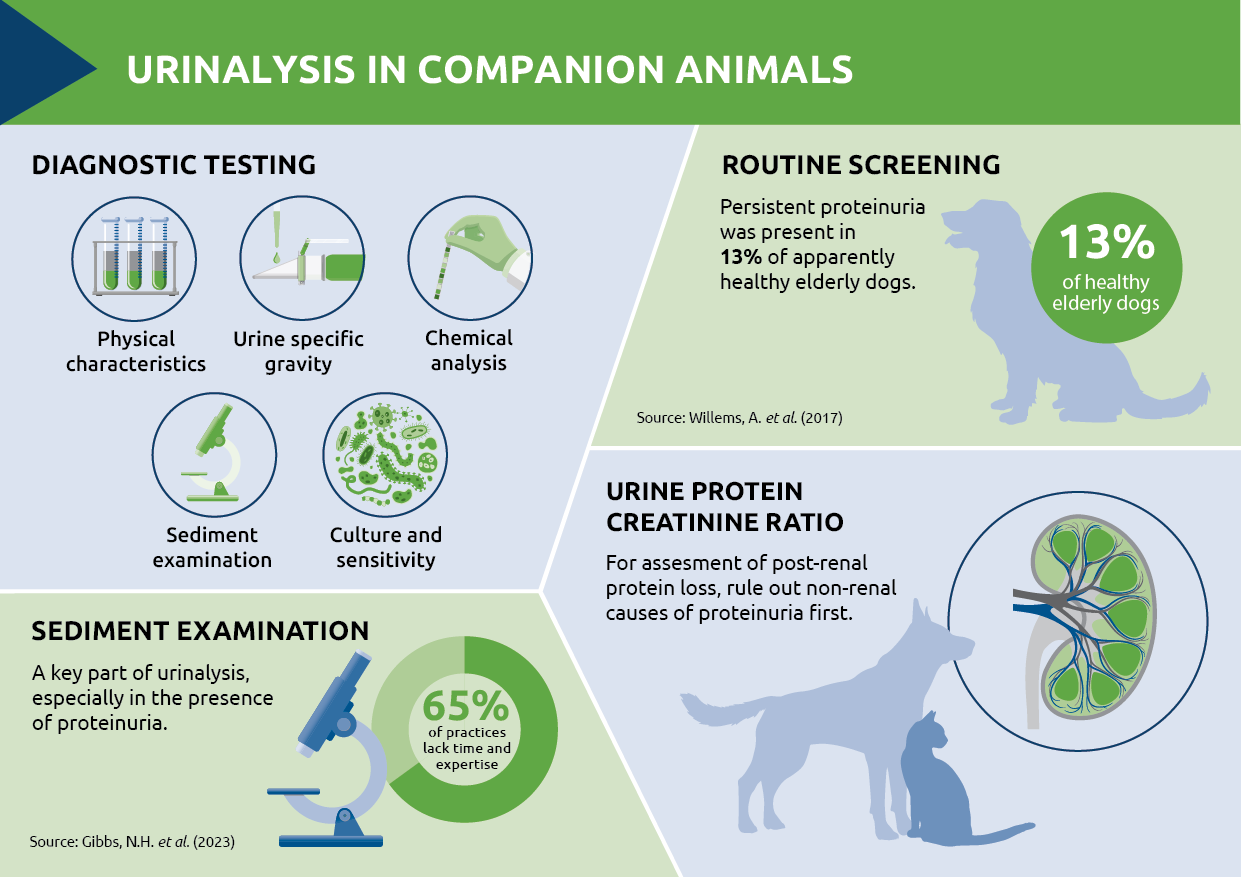

Urinalysis is indicated in many scenarios, from investigating clinical signs such as polyuria and polydipsia (PUPD), to assessing specific urinary tract issues. It should also be part of routine health screenings, particularly in elderly animals, to detect subclinical disease. In one study 13 percent of apparently healthy elderly dogs showed evidence of persistent proteinuria, with a further 18 percent being borderline proteinuric.1 Of these proteinuric dogs, 77 percent were hypertensive, with a systolic blood pressure of 160mmHg or above. Early detection and investigation of proteinuria, which is often linked to renal disease and hypertension, can help prevent progressive injury to multiple organ systems.

Sample collection

Sample collection plays an important role in ensuring accurate and meaningful results, impacting both microscopic findings and culture results (Table 1). Cystocentesis, preferably ultrasound-guided, is recommended when collecting samples for culture as it minimises the risk of contamination. Regardless of the method, ensuring the collection technique is recorded on the laboratory submission form can help with correct interpretation of results.

| Collection method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Free catch | Owner can collect | Risk of contamination |

| Catheterisation | Full bladder not needed | Risk of trauma, iatrogenic infection;requires expertise |

| Cystocentesis | Low contamination risk | Requires expertise,needs sufficient urine in the bladder, not suitable if coagulopathy, risk of bladder trauma and urine leakage |

Table 1. Advantages and disadvantages of urine collection methods

A comprehensive approach

A thorough urinalysis involves four primary components:

- Physical characteristics: colour, transparency (or turbidity) and odour.

- Urine specific gravity (SG) by refractometry: for assessing renal concentrating ability.

- Chemical analysis: using reagent strips to assess parameters including glucose, ketones, protein and pH

- Sediment examination: to identify cells (leucocytes, erythrocytes and epithelial cells), casts, crystals and infectious organisms

Urine specific gravity (SG) key facts

- Dogs: 1.016 – 1.060, Cats: 1.020 – 1.0402

- Use a refractometer, not a dipstick

- Evaluate alongside urea and creatinine levels and hydration status

- Turbidity can affect SG – centrifuge and test the supernatant3

Sediment examination

Urine sediment examination is a key part of urinalysis, especially when protein, leucocytes or erythrocytes are detected during initial investigations or when clinical signs of lower urinary tract disease are present. Reagent strips (dipsticks) can be unreliable for some parameters, such as leucocytes and may give false positives – normal cat urine for example may produce a reaction to the leucocyte square, and this should not be taken as diagnostic for a urinary tract infection (UTI).4 Sediment analysis, however, allows visual inspection of cell types and other elements in the urine, such as casts, crystals and microorganisms.

In urine samples collected via cystocentesis, bacteria should not be present. However, samples obtained through free catch or catheterisation may contain contaminants. The presence of intracellular bacteria, as opposed to extracellular contaminants, is suggestive of an active urinary tract infection (UTI). In such cases, a follow-up sample should be collected by cystocentesis for culture.

Urine should also be checked for the presence of crystals. Struvite crystalluria is a common finding but is often due to precipitation after urine collection. To avoid misinterpretation, examination of samples ‘in-house’ should be performed within one to two hours of collection.

Casts as markers of renal disease

Urine sediment should also be examined for the presence of casts – cylindrical structures formed by mucoprotein in the distal renal tubules.5 These casts, made up of protein and cellular debris, can provide important insights into renal function. For example, hyaline casts, composed of protein, may be seen in small numbers in healthy animals. However, an increased number can be an indicator of renal disease. Cellular casts give additional clues as to the underlying aetiology:

- Epithelial casts suggest renal tubular disease or injury

- Red blood cell casts indicate renal haemorrhage

- White blood cell casts suggest inflammation or infection e.g. pyelonephritis

Urine protein creatinine ratio

It is also essential to perform a urine sediment examination prior to assessing the urine protein creatinine ratio (UPCR). Urine protein creatinine ratio (UPCR) can provide a more accurate assessment of renal protein loss, as it quantifies this loss relative to creatinine concentration. A prior sediment examination helps to rule out post-renal causes of proteinuria, such as inflammation or infection.

Sediment examination is undoubtedly a key part of the diagnostic process but with busy diaries and workforce shortages, 65 percent of practices cite the requirement for staff with the time and expertise to perform these examinations as a barrier.6 Working with an external diagnostic laboratory partner can help to overcome these challenges.

Urine culture guiding treatment

If a bacterial UTI is suspected, whether from history, clinical signs or sediment examination, urine culture is essential to identify the causative organisms and guide appropriate choice of antibiotics. Boric acid is bacteriostatic and for samples with a transit time exceeding two hours, sample tubes containing this preservative should be used. It is worth noting that a high concentration of boric acid is bactericidal to some Gram negative organisms so it is important to fill the tube to the line.

In conclusion

Urinalysis, combined with sediment examination and urine culture remains a cornerstone of veterinary diagnostics, offering insights into renal function, urinary tract health and systemic conditions. Techniques including urine protein electrophoresis (when multiple myeloma is suspected) and PCR for infectious diseases (such as leptospirosis) are additional valuable tools for detecting specific diseases and improving diagnostic accuracy. Leveraging in-house capabilities for time-sensitive tests and using external laboratories as an extension of the practice team can add to available expertise and this collaborative approach can enhance diagnostic efficiency.

References

- Willems, A. et al. (2017) Results of Screening of Apparently Healthy Senior and Geriatric Dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 31(1):81-92

- MSD Veterinary Manual 2024. Table of urine volume and specific gravity. https://www.msdvetmanual.com/multimedia/table/urine-volume-and-specific-gravity

- Christopher, M. Urinalysis and urine sediment. WSAVA Congress Proceedings 2004.

- Caney, S. (2019) Lower urinary tract disease and other urethral disorders in cats. Vet Times 40:27, 5-6

- Whitbread, T. (2015) Urinalysis. MSD Veterinary Manual

- Gibbs, N.H. et al. (2023) Use of urinalysis during baseline diagnostics in dogs and cats: an open survey. J Small Anim Pract. 64(2):88-95

About the author

Dr. Stacey A. Newton BVSc FRCPath CertEM (Int Med) PhD MRCVS is the Head of Clinical Pathology at NationWide Laboratories and has been a Fellow of the Royal College of Pathologists (FRCPath) since 2010. With expertise in both clinical practice and diagnostic pathology, she provides guidance on effective sample collection and interpretation, empowering veterinary professionals to enhance their diagnostic capabilities. Dr. Newton advocates for innovative approaches that integrate in-house services with external laboratory partnerships, thereby improving overall diagnostic efficiency.

Original publication: Veterinary Edge, issue 46, December 2024, pp 24-25