Correlating Cytology and Histology Cases

Author: Sandra Dawson

Correlating histology with cytology can be a tricky but very rewarding experience for the pathologist. Variables such as coexisting inflammation, reactive fibroplasia and haemorrhage can affect the degree to which the true lesion is represented by the cytology. It is also important to have a relevant clinical history and awareness of location of the cytology in order to formulate a meaningful interpretation. The architecture of the histology not only reveals much more information about the diagnosis but may also explain why the cytology interpretation may have been limited. The following fascinating case highlights why this part of the job is both interesting and challenging for the pathologist.

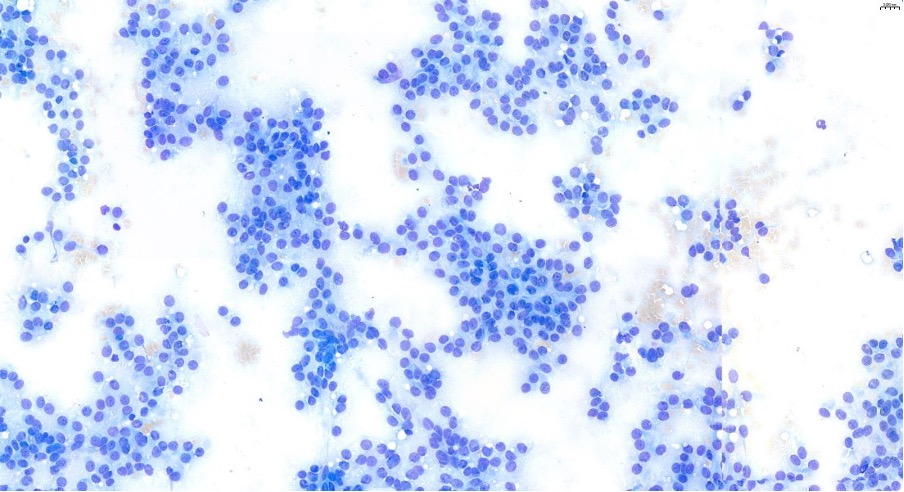

Fine-needle aspirates were submitted from a mass in the scrotal region of a 9-year-old dog which had been neutered 8 years previously. The smears revealed some blood with aggregates of polygonal or slightly spindloid cells forming vague chains and rosettes (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The smears revealed some blood with aggregates of polygonal or slightly spindloid cells forming vague chains and rosettes

The cells had large oval nuclei with stippled chromatin patterns and small nucleoli. They had abundant pale blue cytoplasm with indistinct, wispy borders. The cells were large but uniform. Significant numbers of other cell types were not evident. The aspirates were interpreted as a neoplastic mass of suspected epithelial origin. Histological evaluation of the surgically excised mass was recommended to classify the lesion further and confirm biological behaviour.

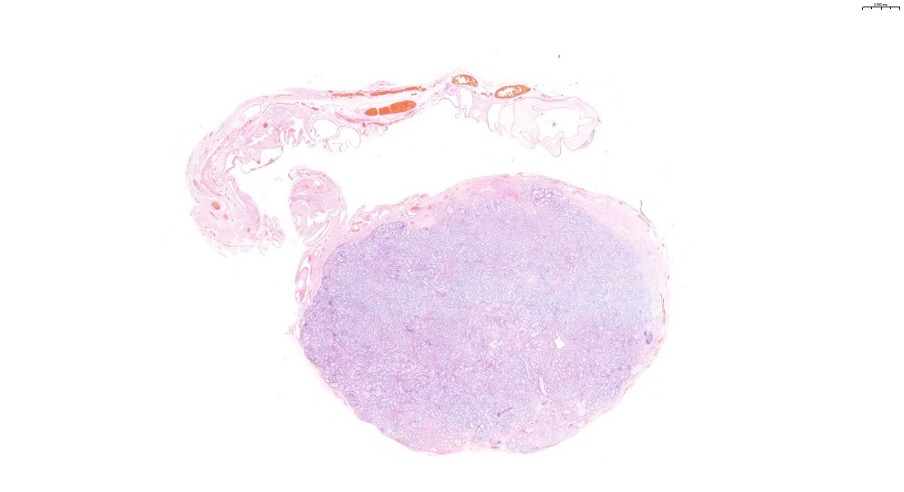

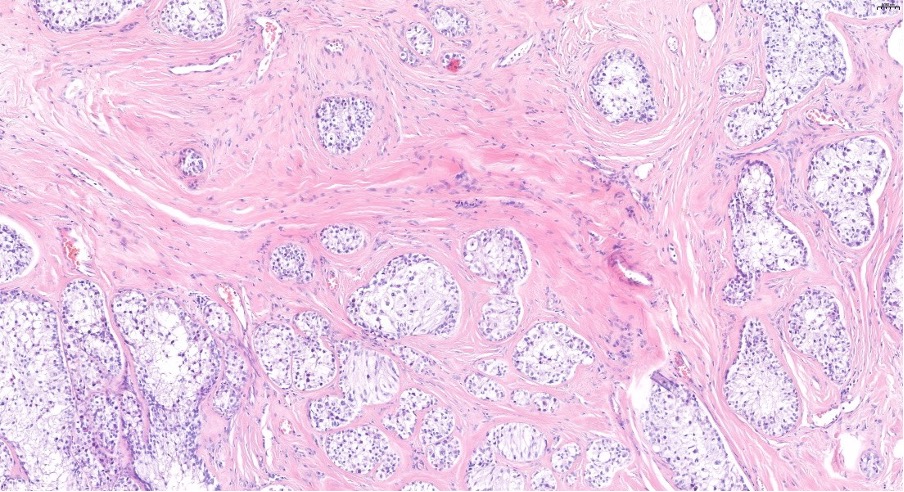

One month later the mass was submitted for histological evaluation. It consisted of a 25 x 15 mm mass with polycystic stalk measuring 37 x 6 mm. Histological evaluation revealed a discrete but nonencapsulated ovoid nodular mass (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Histological evaluation revealed a discrete but nonencapsulated ovoid nodular mass

It consisted of haphazardly arranged, variably sized tubular structures bordered by elongated cells with wispy borders and large oval nuclei. They closely resembled normal Sertoli cells (Figure 3).

Figure 3: The findings closely resembled normal Sertoli cells

Testicular rete tubules, epididymis and tunica albuginea were not identified histologically. Tubules started to push out into the adjacent fibrovascular stroma. The stalk consisted of loose collagen with some muscle. In this area there were dilated blood/lymphatic vessels (varices). At one end there was some compressed connective tissue containing lymphocytes and plasma cells as well as occasional nests of Sertoli cells located very close to small lymphatic vessels. Given the histological architecture of the submission the diagnosis was amended to a Sertoli cell tumour with infiltration, particularly around dilated lymphatic vessels

The Sertoli cells correlated with the spindloid to angular cells observed in the cytology sample. The majority of Sertoli cell tumours have a good prognosis following castration, however malignant tumours are more likely in larger lesions (>2 centimetres) and in extra-testicular lesions (usually intra-abdominal). In this case malignancy was suspected and further clinical staging was recommended. It is unusual that this tumour appears to have developed in a previously neutered dog, which confounded the cytologist. Only the architecture of the histology sample gave the histopathologist the confidence to confirm the diagnosis. Cases such as this are uncommon but do occur and have been published. They are suspected to arise from either embryological ectopic tissue or seeding of testicular tissue transplanted during castration.

References

Extratesticular interstitial and Sertoli cell tumors in previously neutered dogs and cats: A report of 17 cases Angela L. Doxsee, Julie A. Yager, Susan J. Best, Robert A. Foster Canadian Veterinary Journal/ VOL 47 / AUGUST 2006