Disease, diagnostics and the care of senior pets

Age is not a disease. Yet as pets grow older, they become more susceptible to a range of health issues that can impact their quality of life. Thanks to advances in veterinary medicine, including improved surgical techniques, more advanced diagnostics, better nutrition and more, pets are living longer, healthier lives. Over recent years, the lifespan of dogs has increased by approximately five percent while the longevity of cats has seen an even more significant rise, with purebred felines living about nine percent longer and mixed breeds nearly fourteen percent longer.1

Many veterinary practices offer nurse-led ‘senior’ clinics specifically designed to address the unique needs of these older pets, but when is a pet considered senior? With significant variations in breed, type and size, there is no universally fixed age. However, the American Animal Hospitals Association (AAHA) defines the senior stage as the last 25 percent of the expected lifespan,2 meaning it occurs earlier for large and giant breeds than for smaller ones.

Understanding the ageing process

Ageing is a gradual and irreversible pathophysiological process. At the tissue level, this process manifests as pathological changes such as atrophy, fibrosis and fatty infiltration, all of which contribute to the decline in tissue, cellular and organ function.3 While the ageing process itself is not a disease, these changes inevitably increase the risk of age-related health conditions.

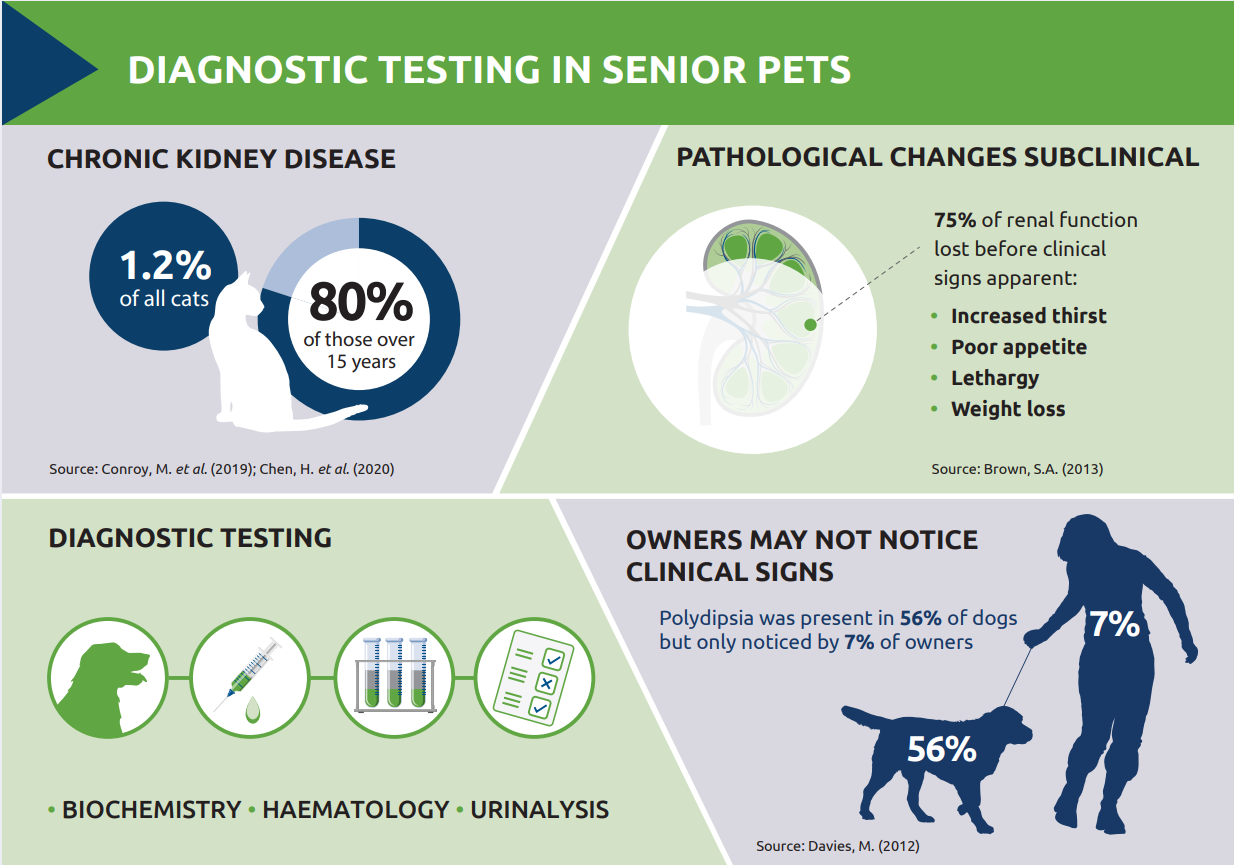

Importantly, these pathological processes often develop silently, with many age-related diseases remaining subclinical for extended periods. For instance, chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a relatively common condition, especially in older cats, but it may not become clinically apparent until approximately 75 percent of renal function is lost.4

The owner’s role in identifying health issues

Even when signs of age-related disease are present, owners may not always recognise or report them. A study involving 45 dogs over nine years of age attending a first-opinion practice, revealed that owners frequently overlooked or misunderstood important clinical signs. For example, only seven percent of owners reported increased thirst, despite it being present in 56 percent of the dogs studied.5 Additionally, none of the owners noticed weight loss in their pets, even though all dogs with a low body condition score, and some with ideal scores, had lost weight prior to screening. This discrepancy highlights that, alongside clinical examination, routine monitoring through laboratory diagnostics has an important role to play.

The power of diagnostic screening

Earlier identification of health issues in senior pets can extend both quality and quantity of life. With this in mind, the primary aim of diagnostic screening is to:

- Detect subclinical disease

- Enable early investigation, diagnosis and intervention

- Identify risk factors

- Identify problems that require ongoing monitoring

If no abnormalities are detected, the screening results can serve as a valuable baseline for future comparison, enabling more precise monitoring of changes over time.

Uncovering hidden health challenges

While the benefits of a thorough clinical examination cannot be overstated, laboratory diagnostics offer key insights that are not always apparent from a physical examination alone. A typical geriatric profile includes parameters to assess renal function, thyroid function, glucose metabolism and other key health indicators. In the aforementioned study of 45 dogs, an average of seven to eight health issues were identified per dog and previously unrecognised problems were found in 80% of cases.

Chronic kidney disease in senior pets

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is one of the most common diagnoses in older cats, with its prevalence rising significantly with age. In fact, studies have shown that while CKD affects approximately one percent of the general cat population,6 its prevalence jumps to as high as 80 percent in those over 15 years.7

Traditional markers like serum creatinine are commonly used to assess renal function, but they have limitations, particularly in the early stages of CKD. In line with the clinical picture, creatinine levels may remain within normal ranges until approximately 75 percent of renal function is lost, making early detection challenging.

The significance of SDMA

This is where symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA) proves invaluable. SDMA is a more sensitive biomarker for renal function that can detect decreases in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) earlier than creatinine; SDMA levels increase when GFR decreases by approximately 40 percent, providing a more timely indication of renal dysfunction. Another advantage of SDMA is that it is less impacted by loss of lean body mass than creatinine, making it a potentially more reliable marker in older pets.

The International Renal Interest Society (IRIS) recognises the importance of SDMA in the early detection and staging of CKD. According to the IRIS guidelines,8 persistently elevated SDMA levels, even when serum creatinine is within normal limits, may indicate early-stage CKD (IRIS stage 1). In reality, creatinine and SDMA levels should be assessed in tandem when investigating, or screening for, renal disease. In addition, levels of both parameters should be assessed on at least two occasions, in a stable, hydrated patient, to confirm persistent elevation.

As pets live longer the need for proactive healthcare becomes increasingly important. Ageing, while not a disease in itself, inevitably leads to physiological changes that heighten the risk of various clinical conditions. Diagnostic testing plays a pivotal role in identifying these issues early, allowing for timely interventions that can significantly enhance both quality and quantity of life in senior pets.

References

- Montoya, M. et al. (2023) Life expectancy tables for dogs and cats derived from clinical data Front. Vet. Sci., Volume 10 https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2023.1082102

- American Animal Hospital Association. AAHA senior care guidelines for dogs and cats. Journal of American Animal Hospital Association. (2005) 41:81–91

- Guo, J. et al. (2022) Aging and aging-related diseases: from molecular mechanisms to interventions and treatments. Sig Transduct Target Ther 7, 391 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-022-01251-0

- Brown, S.A. (2013) Renal dysfunction in small animals. The Merck Veterinary Manual website.

- Davies M. (2012) Geriatric screening in first opinion practice – results from 45 dogs. J Small Anim Pract 53(9):507-13

- Conroy, M. et al. (2019) Chronic kidney disease in cats attending primary care practice in the UK: a VetCompassTM study. Vet Rec 27;184(17):526. doi: 10.1136/vr.105100

- Chen, H. et al. (2020) Acute on chronic kidney disease in cats: Etiology, clinical and clinicopathologic findings, prognostic markers, and outcome. J Vet Intern Med 34(4):1496-1506. doi: 10.1111/jvim.15808

- International Renal Interest Society. IRIS Staging of CKD (2023)

About the author

Sandra Wells

Head of Operations at NationWide Laboratories

BSc (Hons) Applied Biology with Biochemistry

With extensive experience in management roles, including Head of Biochemistry and Group Quality Manager, Sandra is a strategic thinker with a proven track record in the veterinary industry. Now overseeing operations at NationWide Laboratories, she is dedicated to fostering team collaboration and continuous improvement. Her in-depth knowledge of senior pet care, particularly in areas like chronic kidney disease (CKD) and symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA), enables her to enhance diagnostic screening practices that contribute to improved health outcomes for aging pets.

Original publication: Veterinary Edge, issue 44, October 2024, pp 28-29