Diagnostic Dilemmas in Rabbits and Guinea Pigs

Author: Stacey Newton

Rabbits and guinea pigs are popular pets. According to UK Pet Food’s pet population data, there are one million rabbits and 700,000 guinea pigs in the UK. And while they may not yet rival cats and dogs in the popularity stakes, they are becoming more frequent visitors to the consult room.

However, as prey animals, rabbits and guinea pigs are adept at masking signs of illness. Consequently, disease is often advanced by the time it is diagnosed. This makes careful history taking, close observation of behaviour and thorough clinical examinations essential. And alongside this, diagnostic testing, including blood profiles to screen for disease, plays a vital role in uncovering underlying health issues early and improving outcomes for these small but complex creatures.

Foundations of diagnostic testing

Rabbits, guinea pigs and other small herbivores have unique physiologies that reflect their adaption to a diet rich in fibrous plant materials. Despite this, when it comes to diagnostic testing, there are of course, many similarities with other species. Biochemical profiles for rabbits and guinea pigs include assessment of parameters including proteins and electrolytes, urea and creatinine and liver enzymes, providing diagnostic information and assessment of organ function, equivalent to that of other species.

When considering haematology, there are also many similarities. Rabbits, for instance, have typical mammalian erythrocytes – anucleate biconcave discs – like those of cats and dogs. However, their red blood cells have a shorter lifespan of 45 to 70 days, roughly half that of canine red blood cells (110 to 120 days).1 While this has raised questions about whether rabbits are predisposed to anaemia, further studies are needed to determine the clinical significance.

Diagnostic testing in practice

Successfully obtaining blood samples from rabbits, guinea pigs and other small pets requires careful preparation. As prey animals, they are easily stressed, and it is important to have all equipment ready beforehand.

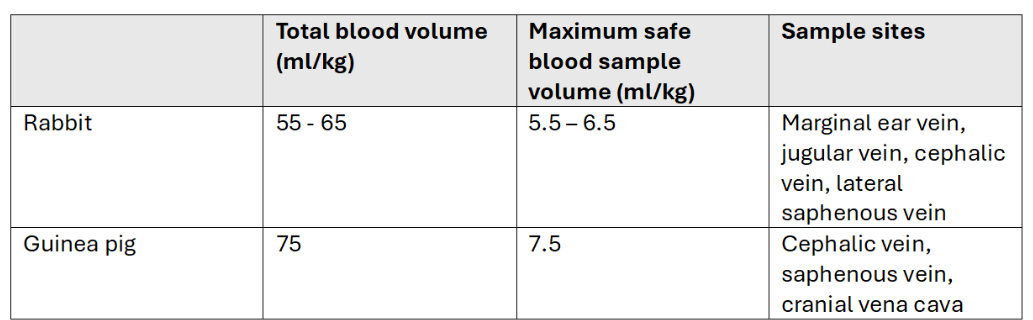

The blood volume of a healthy rabbit is approximately 55 to 65 ml/kg, and up to 10% of this volume can be safely collected (Table 1).2 Common sites for blood collection include the marginal ear vein, jugular vein, cephalic vein and lateral saphenous vein. The latter is often larger than the cephalic vein, making it a practical choice in many cases. Rabbit blood clots rapidly at room temperature and heparinised syringes and needles can also help prevent clotting during the sampling process.2

In guinea pigs, blood sampling can be more challenging due to their smaller size. Small volumes can be collected from the cephalic or saphenous veins without sedation. For larger volumes, the cranial vena cava can be used, though this typically requires anaesthesia. The blood volume of guinea pigs is approximately 75 ml/kg, and up to 1% of their body weight (or 7.5ml/kg) can be safely collected from healthy individuals. In sick animals, this limit reduces to 0.5% of body weight (or 5ml/kg).3

Table 1. Blood sample volumes and collection sites for rabbits and guinea pigs

Glucose and stress responses

It is important to keep stress levels to a minimum when taking samples for diagnostic testing, particularly when assessing blood glucose. Blood glucose levels in rabbits are highly influenced by stress, more so than in many other species. Routine handling can cause glucose levels to rise to 15 mmol/L, while painful conditions can elevate levels to 20 mmol/L or higher. In critically ill rabbits, severe hyperglycaemia – often exceeding 20 mmol/L – is associated with life-threatening conditions such as enterotoxaemia, intestinal obstruction and hepatic lipidosis. In such cases, the degree of hyperglycaemia may serve as a useful prognostic indicator.4

While in many other species, diabetes mellitus is a key differential for hyperglycaemia, in rabbits diabetes mellitus is considered extremely rare. In guinea pigs, however, spontaneous diabetes mellitus is reported to be common.5 Clinical signs are variable, but include polydipsia, and weight loss despite a good appetite. A form of diabetes like type 2 in humans is thought to be most prevalent and affected guinea pigs may respond to weight loss and dietary management.6

Assessing adrenal disease

It is not just diabetes that is uncommon in rabbits; endocrine disorders as a whole are thought to be rare. There are however a number of cases of adrenocortical disease reported in the literature. In neutered ferrets, overproduction of sex hormones by the adrenal glands can lead to hyperplasia and potentially neoplasia due to the absence of negative feedback mechanisms.7 It has been suggested that the pathogenesis may be similar in rabbits and typical signs include persistent sexual behaviour and aggression.

In guinea pigs, hyperadrenocorticism is more frequently reported. Affected guinea pigs exhibit clinical signs including dermatological signs similar to dogs,8 such as non-pruritic hair loss and thinning of the skin, plus polydipsia, weight loss, and lethargy. Diagnosing this condition is now more accessible thanks to salivary cortisol testing offered by NationWide Specialist Laboratories. Saliva samples can be collected on plain cotton buds before and after intramuscular injection of ACTH. This eliminates the need for repeated blood sampling and so reduces stress.

While other endocrine disorders, including hyperthyroidism, have been reported in guinea pigs, they are relatively rare. However, it is worth bearing in mind that endocrine disorders may be underdiagnosed in both guinea pigs and rabbits.

Guinea pig ACTH stimulation test

1. Remove all food 2 hours prior to testing

2. Collect basal saliva sample

· Use a treat to stimulate salivation (but do not feed)

· Ensure cotton buds are ‘wet’ with saliva

3. Inject 5-10µg of synthetic ACTH IM. For a 1kg guinea pig:

· Either 0.04 mL Synacthen (250ug/ml)

· Or 0.1 mL Tetracosactide (100ug/ml))

4. Collect 2 further saliva samples one and two hours later

Source: NationWide Laboratories. Specialist Laboratory Services Information Manual, 20th Edition.

Renal disease in rabbits

While endocrine disease may be rare in rabbits and relatively uncommon in guinea pigs, the same cannot be said for renal disease. Rabbits have renal anatomy which means that neurogenic renal ischaemia occurs more readily.9 In addition, common conditions like gut stasis may lead to pre-renal azotaemia, while chronic renal failure is associated with encephalitozoonosis. Signs of renal disease are broadly similar to other species, namely weight loss, cachexia, polydipsia and lethargy. However, rabbits are unable to vomit and may maintain a good appetite.

Rabbits also have an unusual calcium metabolism; their total serum calcium levels are 30 to 50 percent higher than those of other species and can vary across a wide range. This peculiarity arises because rabbits do not rely on vitamin D for gastrointestinal calcium absorption. Instead, calcium is passively absorbed across the intestinal mucosa, independent of dietary calcium intake. Excess calcium is primarily excreted through the kidneys, a process that makes rabbits more prone to developing calcium-related urinary issues, such as sludgy urine or urolithiasis.

Building expertise

From understanding differences in physiology to mastering the art of stress-free blood sampling, these small pets demand a tailored approach. This article provides a snapshot of diagnostic approaches and considerations for rabbits and guinea pigs. For more detailed advice, consult your specialist laboratory partner. They can act as an extension of the practice team, offering expertise and resources to support the care of small pets with specialist requirements, helping to achieve the best possible clinical outcomes.

About the author: Stacey Newton BVSc FRCPath CertEM (Int Med) PhD MRCVS

Stacey Newton is Head of Clinical Pathology at NationWide Laboratories and a veterinary pathologist with extensive expertise in diagnostic testing. After graduating from Bristol in 1993, she gained clinical experience before focusing on laboratory diagnostics, earning her FRCPath in 2010. With a deep understanding of small animal physiology and disease, she bridges the gap between clinical practice and diagnostic testing, helping to improve patient outcomes.

References

1. Dannemiller, N.G. et al. (2024) Major crossmatch compatibility of rabbit blood with rabbit, canine, and feline blood. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 34: 116–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/vec.13362

2. Varga, M. Textbook of Rabbit Medicine. Chapter 1. Rabbit Basic Science.

3. Rowland, M. (2020), Veterinary care of guinea pigs. In Practice, 42: 91-104. https://doi.org/10.1136/inp.m405

4. Harcourt-Brown, F.M. and Harcourt-Brown, S.F. (2012). Clinical value of blood glucose measurement in pet rabbits. Veterinary Record, 170: 674-674. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.100321

5. Frohlich, J. (2021) Guinea Pigs. MSD Veterinary Manual

6. Kreilmeier-Berger T, et al. (2021) Successful Insulin Glargine Treatment in Two Pet Guinea Pigs with Suspected Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Animals (Basel). 11(4):1025. doi: 10.3390/ani11041025. PMID: 33916377; PMCID: PMC8067123.

7. Mancinelli, E. (2016) Rabbit medicine: latest research on prognostic indicators. Vet Times

8. Jekl, V. (2025) Adrenal Disease in Small Mammals. Vet Clin North Am Exot Anim Pract. 28(1):87-106. doi: 10.1016/j.cvex.2024.07.003. Epub 2024 Oct 15. PMID: 39414475.

9. Harcourt-Brown FM. (2013) Diagnosis of renal disease in rabbits. Vet Clin North Am Exot Anim Pract. 16(1):145-74. doi: 10.1016/j.cvex.2012.10.004. Epub 2012 Dec 13. PMID: 23347542.

Original publication: Veterinary Edge, issue 49, March 2025, pp 40-42