Decoding diabetes mellitus in dogs and cats

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a common endocrinopathy in both dogs and cats. Recent studies suggest one in 200 cats1 and up to one in 300 dogs are affected.2,3 Obesity is a significant risk factor, especially in cats. With nearly half of clinicians reporting an increase in pet obesity in the last two years,4 diabetes is expected to become more prevalent.

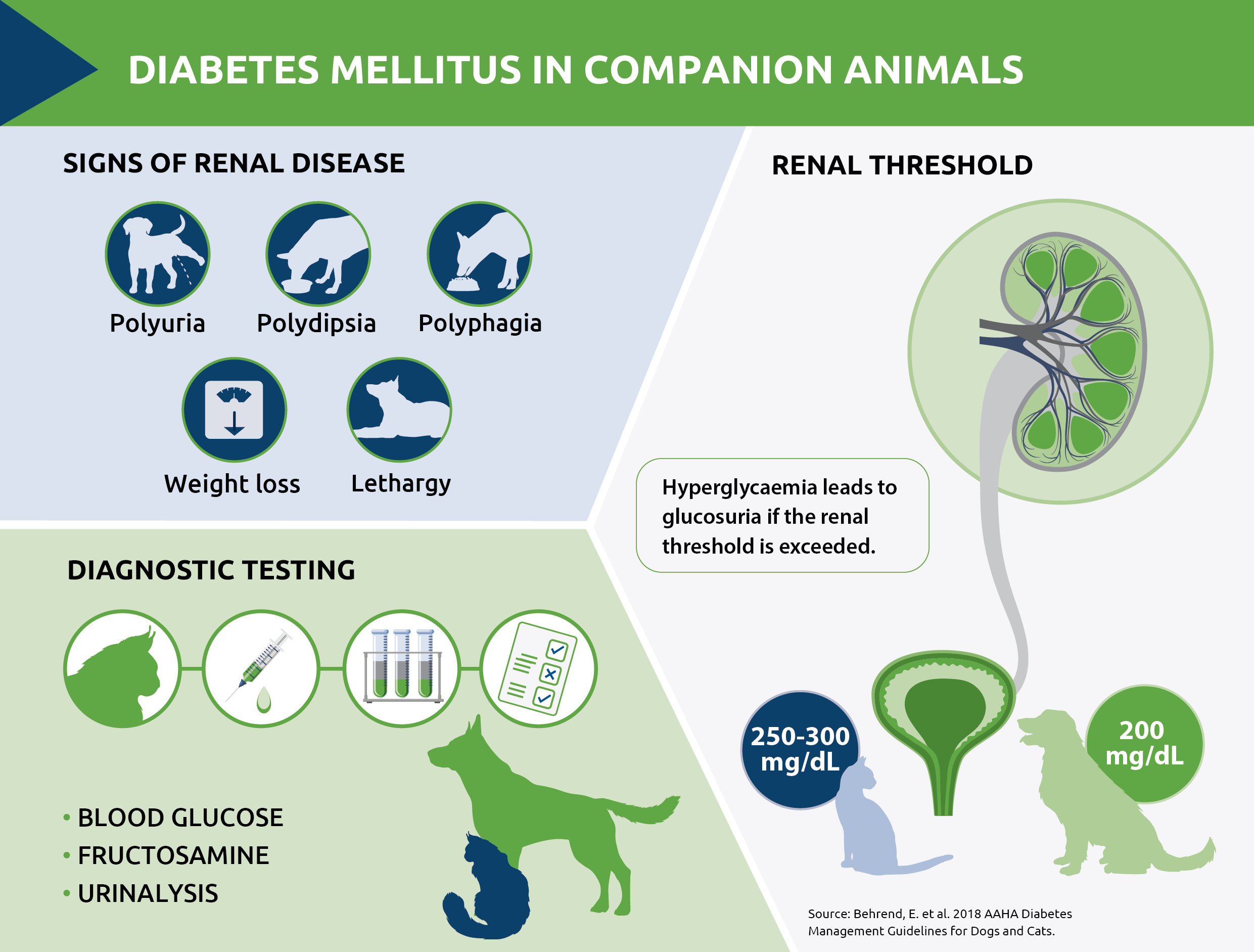

Hyperglycaemia and the renal threshold

The condition is marked by an absolute or relative deficiency of insulin. Produced by pancreatic beta cells, insulin facilitates the uptake of glucose from the bloodstream into cells, where it is used for energy. When insulin is deficient, blood glucose (BG) levels rise, leading to glucosuria if the renal threshold is exceeded. This threshold is approximately 200 mg/dL in dogs and 250–300 mg/dL in cats.5 The osmotic effect of urine glucose results in polyuria and secondary polydipsia.

Spotlight on species differences

Feline DM has distinct differences from canine DM, primarily in its pathophysiology and potential for remission. Most feline cases are caused by insulin resistance and a reduced response to insulin, similar to human type 2 diabetes. Persistent hyperglycaemia in cats initially supresses insulin secretion reversibly and early intervention can lead to temporary or even permanent remission. Prolonged hyperglycaemia, however, causes glucose toxicity and pancreatic beta cell damage. Histologic abnormalities include glycogen deposition and cell death, further reducing insulin secretion. The potential for irreversible changes means that early diagnosis, with effective monitoring and control of blood glucose is crucial for achieving remission.

In contrast, canine DM is usually insulin-dependent due to beta islet cell destruction, similar to type 1 disease in people. This beta cell destruction may be the result of an immune-mediated process.6 While remission is rare in diabetic dogs, early diagnosis is still vital to avoid life-threatening complications like diabetic ketoacidosis.

Key diagnostic criteria

Diagnosing DM involves identifying persistent hyperglycaemia and glucosuria and the European Society of Veterinary Endocrinology has set out criteria to help guide clinicians which are outlined in Table 1.

| Feline diabetes mellitus diagnostic criteria | ||

| Clinical scenario 1 | Blood glucose >= 15 mmol/l (270 mg/dl) | And at least one of:-Increased glycated proteins-Glucosuria on more than one occasion |

| Clinical scenario 2 | Blood glucose between 7 mmol/l and 15 mmol/l | And at least two of:-Classic clinical signs-Increased glycated proteins-Glucosuria on more than one occasion |

| Canine diabetes mellitus diagnostic criteria | ||

| Clinical scenario 1 | Blood glucose >= 11.1 mmol/l | Classic clinical signs of hyperglycaemiaAnd/or-Repeat BG measurement-Increased glycated proteins -Glucosuria |

| Clinical scenario 2 | Fasting blood glucose between 7 mmol/l and 11 mmol/l | Differentiate from stress hyperglycaemia by:-Persistent fasting hyperglycaemia for >24hrs-Increased glycated proteins |

Table 1. Criteria for diagnosing diabetes mellitus in dogs and cats7

Blood glucose testing: from spot checks to curves

Measuring BG is straightforward. A single (or ‘spot’) BG reading is easy to obtain with only a small blood volume required and patient-side results available rapidly. However, while a single reading is useful for checking for hypoglycaemia, it only provides a ‘snapshot’ of the whole picture and does not differentiate stress hyperglycaemia from elevated BG due to DM.

A blood glucose curve, with serial measurements plotted over 12 to 24 hours, is more useful, especially when investigating an unstable diabetic patient. In these cases, BG curve readings taken on several days over a two-to-three-week period, provides a more complete clinical picture.8

Stress hyperglycaemia can impact BG readings, especially in cats in a veterinary setting, where levels may increase by as much as 10mmol/l above the baseline, with values up to 16 mmol/l in healthy non-diabetic cats. Physiological stress can also affect results, with BG levels as high as 34 mmol/l possible in sick, non-diabetic cats.9

Monitoring glycated proteins

For a more accurate assessment of a patient’s glycaemic status, testing for glycated proteins, like fructosamine should be considered. Fructosamine is a serum protein formed by an irreversible, non-enzymatic glycosylation of serum proteins, predominantly albumin. Given that albumin has a half-life of approximately eight days in both dogs and cats,10 fructosamine levels reflect the average blood glucose concentration over the preceding one to two weeks.

Fructosamine measurement helps determine whether hyperglycaemia is stress-induced and transient or reflects a persistent hyperglycaemia due to disease. Furthermore, a 2023 study concluded that serum fructosamine was moderately predictive of diabetes mellitus control, and improved clinical signs over repeated follow-up visits were associated with decreases in fructosamine.11 Combining fructosamine monitoring with BG curves provides a more reliable picture and can help to inform treatment decisions.

Urinalysis: a comprehensive approach

If BG remains above the renal threshold for a prolonged period of time, glucose spills over into the urine. In conjunction with blood testing, the presence or absence of glucosuria is an important part of the diagnostic process. Urine testing is also a quick and easy means of checking for the presence of ketones.

As well as testing for glucosuria and ketonuria, full urinalysis including microscopy and bacterial culture forms part of a comprehensive diagnostic plan. Urinary tract infection (UTI) is common in dogs with diabetes mellitus and may cause insulin resistance. Therefore, bacterial culture is recommended, particularly in unstable diabetics or those with poor control of clinical signs.

Some patients may have a positive urine culture but no signs of UTI. This is termed subclinical bacteriuria. There is some debate as to whether stable diabetics with subclinical bacteriuria warrant treatment. Although there is a potential risk of ascending infection, treating dogs with subclinical infection may result in colonisation of the urinary tract with resistant bacteria.12 Each patient should be considered on an individual basis.

Assessing for co-morbidities

Age is a significant risk factor for the onset of DM and many diabetic patients will have age-associated comorbidities. All newly diagnosed patients should be evaluated for concurrent disease, especially where this may increase the risk of insulin resistance or ketoacidosis. A minimum database should include full haematology and biochemistry to screen for conditions such as:

- Pancreatitis

- Other endocrine disease e.g. hyperadrenocorticism

- Urinary tract infection

- Infectious disease

- Neoplasia

Beyond basic blood tests

Further testing may be necessary for unstable diabetic patients, or those requiring increasing insulin dosages. Measuring insulin antibodies can be useful for investigating an increased dose requirement, although the clinical significance of the presence of insulin antibodies is unclear.13,14 Other tests including canine and feline insulin-like growth factor are indicated where there is clinical suspicion of pituitary dwarfism or acromegaly and in insulin-resistant diabetic cats. For complex cases and further discussion of testing, consulting a specialist laboratory is advisable.

References

- O’Neill, D.G. et al. (2016). Epidemiology of Diabetes Mellitus among 193,435 Cats Attending Primary-Care Veterinary Practices in England. J Vet Intern Med;30, p 964–972

- Fall, T. et al. (2007) Diabetes mellitus in a population of 180,000 insured dogs: incidence, survival, and breed distribution. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 21:1209

- Mattin, M. et al. (2014). An epidemiological study of diabetes mellitus in dogs attending first opinion practice in the UK. Vet. Record 174: 349

- PDSA Paw Report 2023

- Behrend, E. et al. 2018 AAHA Diabetes Management Guidelines for Dogs and Cats

- Gilor, C. et al. (2016) What’s in a Name? Classification of Diabetes Mellitus in Veterinary Medicine and Why It Matters. J Vet Intern Med. 30(4):927-40

- European Society of Veterinary Endocrinology. ALIVE criteria for diagnosing DM in cats. ALIVE criteria for diagnosing DM in dogs 2021

- Fletcher, J. Monitoring Canine and Feline Diabetics: Beyond the Glucose Curve. WSAVA Congress Proceedings, 2019

- Rand, J. S. & Martin, G. Current Understanding of Feline Diabetes Mellitus. WSAVA Congress Proceedings 2004.

- Thoresen, S.I. & Lorenzen, F.H. (1997) Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus in Dogs Using Isophane Insulin Penfills and the Use of Serum Fructosamine Assays to Diagnose and Monitor the Disease. Acta Vet Scand 38, 137–146

- Kuzi, S. et al. Clinical utility of serum fructosamine in long-term monitoring of diabetes mellitus in dogs. Vet Rec. 2022;e2236.

- Senior, D. Management of subclinical bacteriuria. Clinician’s Brief 2018

- Davison, L.J. et al. (2003) Anti-insulin antibodies in dogs with naturally occurring diabetes mellitus. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 91:53-60

- Davison, L.J. et al. (2008) Anti-insulin antibodies in diabetic dogs before and after treatment with different insulin preparations. J Vet Intern Med 22(6):1317-1325

About the author:

Helen Evans

Laboratory Manager at NationWide Specialist Laboratories

Helen Evans has a background in biological sciences and began her career developing assays at St Thomas’ Hospital in London. She then transitioned to a veterinary clinical laboratory, a setting where she spent over 20 years. As a co-founder and a manager at NationWide Specialist Laboratories, Helen has successfully grown the laboratory, offering unique assays. With extensive expertise in endocrinology, biochemistry, and veterinary medicine, including canine and feline diabetes mellitus, Helen provides valuable insights on this chronic disease’s growing prevalence.

Original publication: Veterinary Edge, issue 42, August 2024, pp 24-26