Improving accuracy in veterinary cancer diagnostics

Author: Sandra Dawson

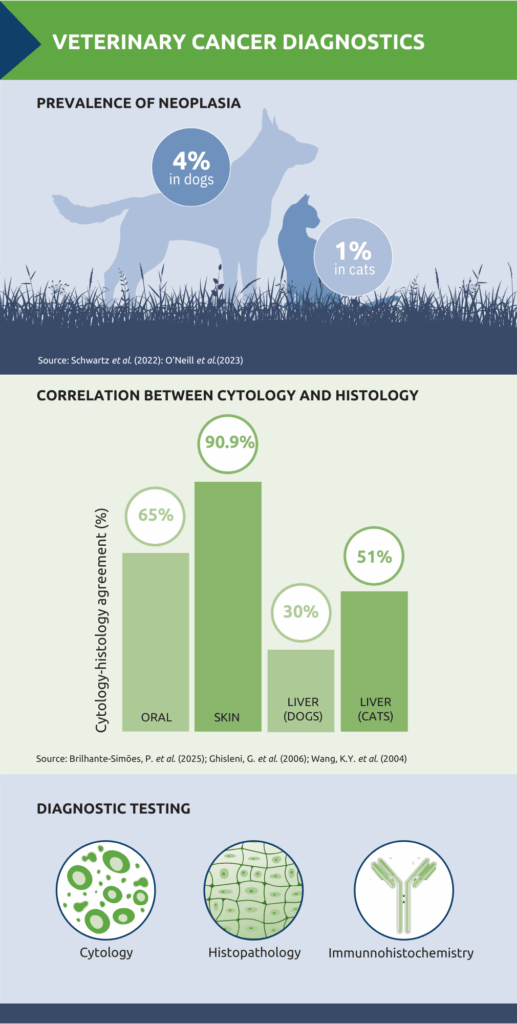

Lumps and bumps are among the most common reasons for veterinary consultations. Reported prevalence figures vary, but several studies give an indication of the scale of the problem. In dogs, the lifetime prevalence of malignant tumours has been estimated at 29.7 per 1,000, with benign tumours at 14.7 per 1,000.1 In cats, one study estimated an overall prevalence of around 1%.2 Despite differences in methodology and population, what is not in doubt is that early and accurate diagnosis is crucial – both to guide treatment planning and to give owners clarity.

Cytology as a first line test

Cytology is an excellent first-line diagnostic tool in the investigation of suspected neoplasia. It is rapid, minimally invasive and cost effective, making it ideal for screening and for guiding further diagnostics. Various different sampling techniques can be used with the precise technique depending on factors such as the physical characteristics of the lesion and the likelihood of blood contamination.3

Impression smears are useful for inflammatory or ulcerated lesions but of limited value in veterinary cancer diagnostics as deeper more representative cytological material is not obtained.4 One exception is at the time of biopsy, when the cut surface of a lesion can be applied to a slide, to allow immediate assessment.

Fine needle aspiration in practice

Fine needle aspiration (FNA) is the most widely used technique for cytological sample collection, suitable for visible or palpable masses and, with ultrasound guidance, for

deeper lesions. A 21 or 23 gauge needle is recommended, as smaller gauges are more likely to cause cell damage. Some tissues, particularly those composed of mesenchymal cells, have a naturally low cell harvest because the cells adhere tightly to each other and do not exfoliate easily. In such cases, a larger-bore needle and suction may be required.3

Correct technique is essential. In one study, 17% of samples submitted to a laboratory had inadequate cellularity.5 Whatever technique is used, accurate cytological interpretation also depends on clinical context, including history and lesion-specific details.6

Tips for cytology on solid masses

– Use a 21-23 gauge needle for most FNAs, with or without a 5ml syringe

– Needle-only technique can reduce haemodilution and lysis of fragile cells

– If using a syringe, release suction before withdrawing the needle

– For poorly exfoliative tissues, consider a larger bore needle and apply suction

– Prepare smears using standard or ‘squash’ technique

– Make multiple smears to maximise diagnostic yield

– Ensure slides are unstained and air-dried

– Avoid exposure to formalin

– Label slides clearly

FNA generally carries little risk to the patient, but the technique may be contraindicated if there is evidence of defective haemostasis. To reduce the risk of complications, the platelet count should be >10 per field (using the x100 oil objective).

However, while cytology can help determine the type of pathological process (inflammatory, infectious or neoplastic), evaluation of tissue architecture through biopsy and histopathology is often required for definitive diagnosis.

Correlation and complementarity

While cytology is invaluable for rapid assessment, histopathology remains key for characterising neoplastic disease. By preserving tissue architecture, histology provides the additional information needed to determine tumour type, grade, and invasiveness – details that cytology alone cannot deliver. The two techniques therefore work best in combination, with cytology guiding early decisions and histology confirming and refining the diagnosis.

Several studies have explored the level of concordance between cytology and histology. In oral lesions, cytology demonstrated high accuracy (87.4%) in distinguishing cancerous from non-cancerous changes, with complete agreement with histopathology in 65% of cases.7 A retrospective study of palpable cutaneous and subcutaneous masses in 242 dogs and 50 cats reported a similarly strong relationship: cytologic diagnosis was in agreement with histopathology in 90.9% of cases.5

However, the strength of correlation is not uniform across all tissue types. In liver disease, for example, a study comparing FNAs with biopsy samples found agreement in only 30% of dogs and 51% of cats.8 Part of the challenge is that hepatic pathology can be focal rather than diffuse, meaning aspirates may not always be representative of the underlying process. In addition, many liver diseases require evaluation of tissue architecture which cannot be assessed on cytology alone.

The role of immunohistochemistry

Even when histopathology is available, there are occasions when tissue architecture alone does not provide a definitive answer. Some tumours are so poorly differentiated that no typical features are present or exhibit multiple conflicting features, making it difficult to establish origin or behaviour on haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining alone. In these cases, immunohistochemistry (IHC) can be an invaluable additional tool.

IHC works by detecting tissue antigens using targeted antibodies in histological sections. By binding to proteins specific to cell type or origin, such as cytokeratins in carcinomas or lymphoid markers in round cell tumours, IHC can help confirm whether a lesion is neoplastic and define its lineage. The antigen-antibody complex is visualised using a conjugated enzyme that catalyses a colour-producing reaction, allowing neoplastic cells to be identified microscopically.

The use of IHC is expanding in veterinary oncology as the range of commercially available antibodies increases and costs become more accessible. It can be used to identify neoplastic cell types, refine tumour classification to guide prognosis and highlight uniform or mixed cells populations thus helping to distinguish between reactive and neoplastic processes. In lymphoid proliferations in particular, immunophenotyping is often required to determine lineage (B-cell vs T-cell) which can have important prognostic and therapeutic implications. IHC is not simply ‘belt and braces’ but often the key to achieving an accurate, clinically useful diagnosis.

An integrated approach

Cytology, histopathology, and immunohistochemistry are not competing tools but complementary ones. Integrating these approaches supports earlier recognition of neoplasia, accurate diagnoses, and well-informed treatment planning – ultimately improving outcomes for pets and giving owners clarity and confidence.

About the author

Sandra Dawson BSc BVMS FRCPath MRCVS

Sandra graduated from Aberdeen and Glasgow Universities with degrees in agriculture and veterinary medicine. After working in mixed practice, she completed a residency in veterinary pathology at Edinburgh University, where she also lectured in reproductive pathology. Following five years in industry, during which she gained her FRCPath, Sandra joined NationWide Laboratories. In 2011 she was appointed to the Royal College of Pathologists board of examiners in the speciality of small domestic animals. Sandra specialises in histopathology, working with surgical biopsies and fine needle aspirates across a wide range of species.

References

1. Schwartz, S.M. et al. (2022) Lifetime prevalence of malignant and benign tumours in companion dogs: Cross-sectional analysis of Dog Aging Project baseline survey. Vet Comp Oncol. 20(4):797-804. doi: 10.1111/vco.12839. Epub 2022 Jun 2. PMID: 35574975; PMCID: PMC10089278.

2. O’Neill, D.G. et al. (2023) Commonly diagnosed disorders in domestic cats in the UK and their associations with sex and age. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 25(2). doi:10.1177/1098612X231155016

3. Whitbread, T. Post, K. & Hendrix, C. (2025) Cytology. MSD Veterinary Manual. https://www.msdvetmanual.com/clinical-pathology-and-procedures/diagnostic-procedures-for-the-private-practice-laboratory/cytology

4. Garland, M. (2012). Cytology for veterinary nurses Part 1. Basic sampling techniques and cell identification. Veterinary Nursing Journal, 27(5), 187–188. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2045-0648.2012.00174.x

5. Ghisleni, G. et al. (2006) Correlation between fine needle aspiration cytology and histopathology in the evaluation of cutaneous and subcutaneous masses from dogs and cats. Vet Clin Pathol. 35(1):24-30. doi:10.1111/j.1939-165x.2006.tb00084.x

6. Fraser, C. & Meichner, K. (2023) Insights in clinical pathology. Skin “lumps and bumps” cytology. Today’s Veterinary Practice. Sept/Oct 2023; 68-77

7. Brilhante-Simões, P. et al. (2025) Association Between Cytological and Histopathological Diagnoses of Neoplastic and Non-Neoplastic Lesions in Oral Cavity from Dogs and Cats: An Observational Retrospective Study of 103 Cases. Vet Sci. 21;12(2):75. doi: 10.3390/vetsci12020075. PMID: 40005835; PMCID: PMC11861943

8. Wang, K.Y. et al. (2004) Accuracy of ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of the liver and cytologic findings in dogs and cats: 97 cases (1990-2000). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1;224(1):75-8. doi: 10.2460/javma.2004.224.75. PMID: 14710880.

Original publication: Veterinary Edge, issue 57, November 2025, pp 48-49