Diagnostic Approaches to Gastrointestinal Disease in Cats and Dogs

Author: Jana Leontescu

Gastrointestinal (GI) disorders are among the most common clinical presentations in small animal practice, ranging from acute self-limiting conditions to chronic diseases requiring extensive investigation and management. Enteropathies, for example, have a prevalence of around 10 percent in dogs, second only to dental disorders (14.1%) and skin disorders (12.58%).1 For cats the picture is similar, with a prevalence of 8.5 percent.2

Determining the underlying cause of GI disease can be challenging. However, a structured diagnostic approach, incorporating a detailed history and thorough clinical examination, alongside appropriate laboratory diagnostics, is essential to guide treatment and improve patient outcomes.

History and clinical signs

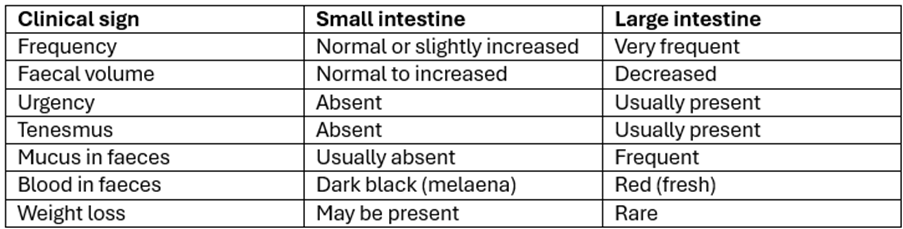

A thorough history is crucial, helping to formulate a problem list and differentiate between a myriad of potential causes, including dietary indiscretion, infectious agents, and systemic diseases. Important aspects to consider include vomiting frequency, as well as the duration, severity, and characteristics of diarrhoea (see Table 1). Dietary history, exposure to infectious agents, and any previous treatments should also be considered. Clinical examination should assess hydration status, body condition, abdominal pain, and any extra-intestinal signs such as fever or jaundice, which may indicate systemic involvement.

Table 1. Differentiation of small intestinal from large intestinal diarrhoea.3

Laboratory diagnostics

A minimum database, including haematology and serum biochemistry is important as the next step in the diagnostic work-up. While many chronic GI cases show no abnormalities on these initial diagnostics, routine blood screening helps to rule out extra-gastrointestinal causes and identify non-specific changes, such as:

- Dehydration: haemoconcentration, elevated total protein and pre-renal azotaemia due to fluid loss.

- Chronic inflammation: mild non-regenerative anaemia is a common finding in chronic inflammatory disorders.

- Gastrointestinal haemorrhage: elevated urea, disproportionate to elevations in creatinine may indicate GI bleeding; microcytic hypochromic anaemia suggests chronic blood loss.

- Electrolyte disturbances:

- Hypokalaemia may result from fluid losses from the GI tract.

- Hyponatraemia may result from severe fluid loss or secondary to endocrine disorders such as hypoadrenocorticism.

- Hypochloraemia may result from vomiting of gastric contents, especially in cases of upper GI obstruction.4

Total protein, hypoalbuminaemia and protein-losing enteropathy

Low albumin levels are a not uncommon finding on initial diagnostic screening. Chronic hypoalbuminaemia may occur due to intestinal loss (protein-losing enteropathy) but can also occur due to loss from the kidneys (protein-losing glomerulopathy) or due to decreased production from the liver. Identifying the source of the protein loss is essential for narrowing down the differential list.

Protein-losing enteropathy (PLE) is a diverse group of disorders characterised by enteric protein loss. The three most common causes are inflammatory bowel disease, lymphoma and lymphangiectasia and differentiating between these requires intestinal biopsies and histopathology.5 It is also worth noting that low serum albumin has been associated with negative clinical outcomes, including a poor response to dietary and drug therapies.

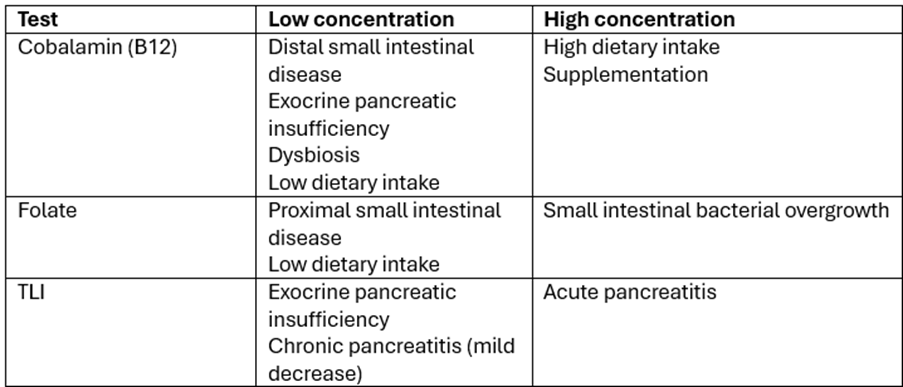

B12, folate and TLI in the diagnosis of gastrointestinal disease

In many cases, initial screening tests can help guide further diagnostics, including GI-specific testing. With this in mind, assessing serum levels of vitamin B12 (cobalamin), folate, and trypsin-like immunoreactivity (TLI) is a useful step in the diagnostic process (Table 2).

Vitamin B12 and folate are absorbed in different parts of the intestine, and their levels can help localise gastrointestinal pathology. B12 is absorbed in the ileum with the help of intrinsic factor, a protein primarily produced by the pancreas. When levels are low, it can indicate ileal disease, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI), or dysbiosis. Folate, in contrast, is absorbed in the proximal small intestine (jejunum). A decrease in folate levels suggests impaired jejunal absorption, whereas an increase may point towards small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO).

TLI measures serum trypsin and trypsinogen concentrations and is considered the test of choice for diagnosing exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI).6 Trypsinogen is produced exclusively by the pancreas, and its circulating levels reflect exocrine pancreatic function. A markedly low TLI level confirms EPI, as affected animals are unable to produce sufficient digestive enzymes. Mildly decreased TLI levels may be seen in cases of chronic pancreatitis, but they are not necessarily indicative of EPI. If TLI levels are within the normal range, EPI can be ruled out as a cause of gastrointestinal signs.

Table 2. Interpretation of cobalamin, folate and TLI levels.

Faecal screening for pathogens

While many cases of diarrhoea are self-limiting, where clinical signs persist, infectious agents may be on the differential diagnosis list and faecal diagnostic tests play a key role in identifying (or ruling out) these potential pathogens. Traditional techniques, such as microscopic examination can detect common intestinal parasites, including Giardia, Cryptosporidium, and coccidia. However, sensitivity and specificity have significantly improved with the advent of advanced diagnostics, including polymerase chain reaction (PCR) panels. The most commonly used faecal PCR panels are designed to identify a broad range of pathogens, ensuring a comprehensive diagnostic approach:

Canine diarrhoea panel: canine parvovirus (CPV), canine distemper virus (CDV), enteric coronavirus, Salmonella, Giardia, Cryptosporidium, Campylobacter jejuni, and Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin.

Feline diarrhoea panel: feline panleukopenia virus (FPV), feline coronavirus, Salmonella, Giardia, Cryptosporidium, Toxoplasma gondii, Tritrichomonas foetus, Campylobacter jejuni, and Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin.

In conclusion, gastrointestinal disorders in cats and dogs present a range of challenges and require careful investigation. A thorough history, clinical examination, and appropriate diagnostic tests are essential in identifying the underlying cause and guiding effective treatment. With a structured approach, including tests for vitamin B12, folate, and TLI levels, along with faecal screening and imaging, clinicians can better localise gastrointestinal pathology and differentiate between various conditions. Early and accurate diagnosis leads to more targeted management, ultimately improving the outcome for patients.

References

1. O’Neill, D.G. et al. (2021) Prevalence of commonly diagnosed disorders in UK dogs under primary veterinary care: results and applications. BMC Vet Res 17, 69 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-021-02775-3

2. O’Neill, D.G. et al. (2023) Commonly diagnosed disorders in domestic cats in the UK and their associations with sex and age. J Feline Med Surg 25(2):1098612X231155016. doi:10.1177/1098612X231155016

3. MSD Veterinary Manual. Differentiation of small intestinal from large intestinal diarrhoea.

4. Cook, A. & Heinz, J. (2022) Evaluation and management of the hypochloremic patient. TVP.

5. Boatright, K. (2023) A stepwise approach to hypoalbuminemia. DVM360

6. Cridge, H. et al. (2024). Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency in dogs and cats. JAVMA 262(2), 246-255 https://doi.org/10.2460/javma.23.09.0505

Original publication: Veterinary Edge, issue 50, April 2025, pp 48-50

About the Author

Jana Leontescu BSc, MRCVS has a background in clinical practice in both Romania and the UK. Her interest in veterinary science led her to transition from practice to diagnostic pathology, joining NationWide Laboratories as part of the microbiology team with a focus on parasitology. Now training as a Clinical Pathologist, she is working towards board certification, expanding her expertise in laboratory diagnostics across a range of disciplines. Her experience on both sides of veterinary medicine gives her a well-rounded perspective on the challenges of diagnosing and managing disease.